By Matthias Röhrig Assunção.

The small roda (circle) of capoeira, as opposed to the big circle of life, is a metaphor often used by capoeira mestres and practitioners. This image points to the constant interaction between the practice of capoeira and society at large. In the case of the time frame of our research project – 1948-1984 – a look at these complex and multidimensional relationships helps us understand the development of “contemporary capoeira” in Rio de Janeiro.

Learn more

about the importance of capoeira in carioca society and culture

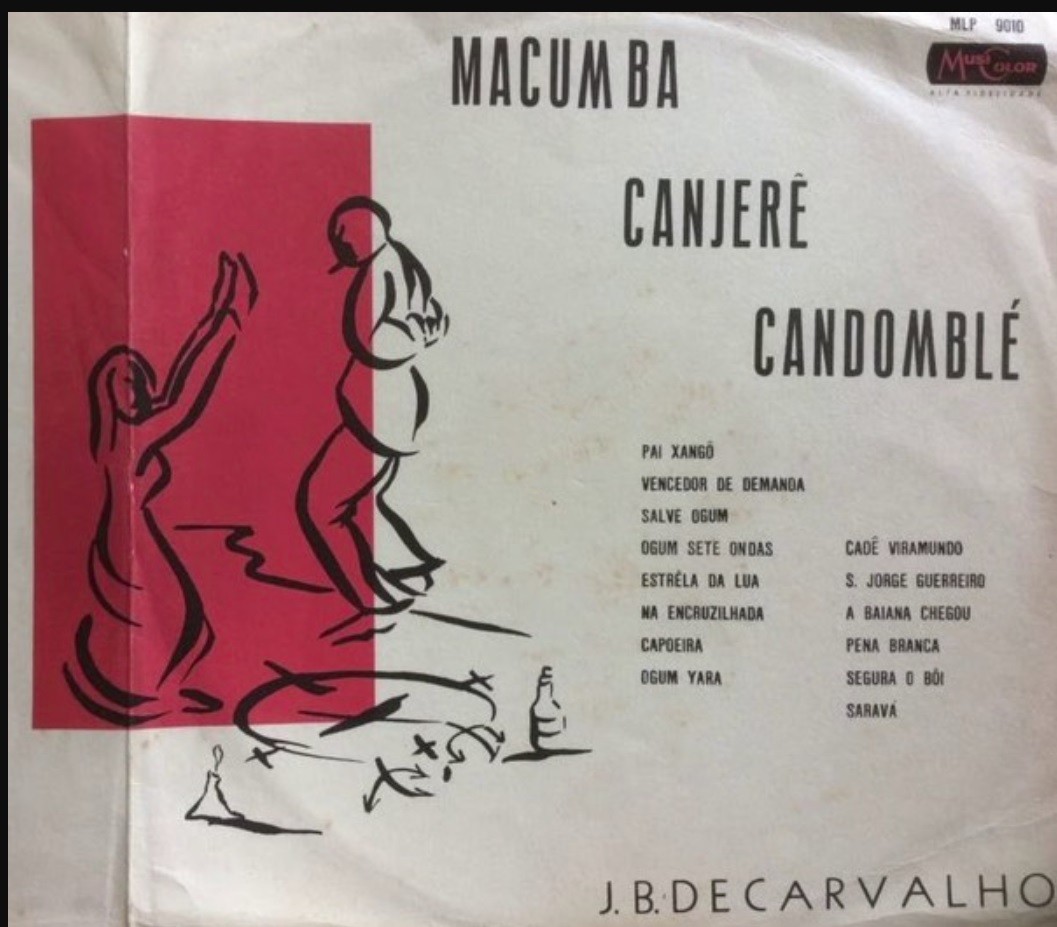

As with all manifestations of popular culture, capoeira in Rio de Janeiro has never existed in isolation. It has always been associated with other forms, such as samba, batucada, pernada carioca, umbanda and candomblé, to list only the most well-known connections. This insertion unfolded into a process of cultural circulation in which each cultural expression borrowed certain elements from other cultural forms. Capoeira movements were exchanged with those from samba and pernada, and its lyrics can be found in samba and jongo.

It was during Carnival that this relationship was most visible

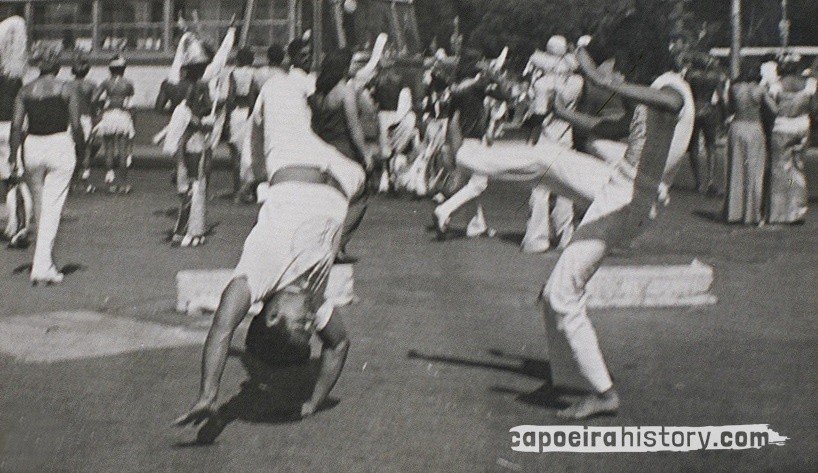

It was during Carnival that this relationship was most visible, when samba schools, such as Mangueira, and bloco de embalo (more informal samba groups which don’t compete in the official parade), such as Bafo da Onça and Cacique de Ramos, welcomed the resurgent practice of capoeira in the 1960s.

In the photo, Masters Paulão and Bourgeois, in the Cacique de Ramos block parade (bloco de embalo), 1970s. Paulão Muzenza collection.

At the same time, capoeira entered the ring.

The first confrontations with fighters from other martial arts already took place in the First Republic. Everyone always remembers Ciríaco’s famous encounter with Count Koma, in 1909, in Rio de Janeiro, because in that case Brazilian capoeira won.

In the image, the newspaper O Malho, of 20/08/1910, brings a photo of Ciriaco, who became a celebrity after the victory over Sada Miako, with the news that the “master of capoeiragem” was resting from the fight on a farm in Minas Gerais.

.

There were, however, many other prize fightings, in Salvador, in Rio de Janeiro, in São Paulo and in Belém, in which not only Mestre Bimba’s pupils participated, but also angoleiros. And there is no point in denying it: many times the capoeiristas lost, especially against jiu-jitsu practitioners. The angoleiros and Bimba himself eventually withdrew from the ring, in Salvador, as did Artur Emídio, shortly afterwards, in Rio. But those confrontations in the ring and the wider relationship between capoeira and other martial arts were very important in defining the directions capoeira itself would take during the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. Capoeira also contributed to the Brazilian style of jiu-jitsu, BJJ, as well as to the emergence of vale-tudo and MMA, as shown in more detail in recent research by Elton Silva and Eduardo Corrêa, published in the book Muito antes do MMA: O legado dos precursores do Vale Tudo no Brasil e no mundo.

Capoeira and MPB (Brazilian Popular Music)

Capoeira was also present, from the beginning, in emerging musical styles such as Bossa Nova and Brazilian Popular Music (MPB). The pioneer, as far as we know, was J. B. de Carvalho, known in Rio de Janeiro for recording macumba songs. In 1955, still in 78 rpm format, he sang: “Capoeira toma sentido/e eu vou lhe derrubar” (Capoeira makes sense/and I’ll knock you down) in a composition he wrote with Walter Tourinho and Guará, which was re-recorded in 1961. Then there was Capoeira na Pituba (Clélio Ribeiro – Lauro Paiva) recorded by Maestro Paulo Alencar and his orchestra (1961).

But the first capoeira-themed recording to really become a success, to the point of being translated into English, was Água de Beber, by Tom Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes, interpreted by João Gilberto and released in 1963. However, capoeira here is still more alluded to than explicit. Not everybody knew then that capoeiras called each other “camarada” or “camará” and that “água de beber” is a refrain from a capoeira song (chula).

In 1964 several songs were released with themes related to capoeira. Jorge Ben released Capoeira. The title is followed by a refrain that refers directly to the roda: “Vamos embora camarada, vamos sair dessa jogada” (“Let’s go comrades, let’s get out of this game”), already using the language of capoeira in the lyrics.

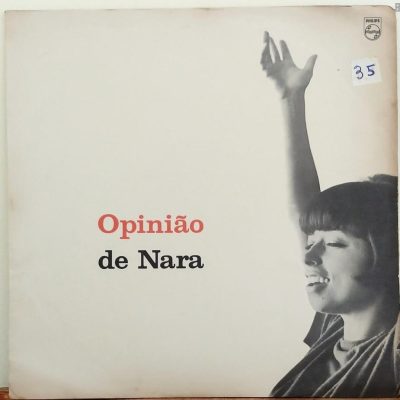

Nara Leão went even further by recording, in her second record, the song Berimbau (1964), which she also sang in her debut as a singer, in a night club in Copacabana. The song by Baden Powell and Vinicius de Moraes used capoeira lyrics of popular domain. This record, considered by many as the beginning of MPB, was very successful (CABRAL, Nara Leão, p. 273). Nara included the same song in her LP Opinião, released nine months later, still in 1964. This LP also has the song Na roda da capoeira, which was even more faithful to the instruments and berimbau sounds of capoeira.

From then on, many MBP stars composed or recorded songs themed on capoeira: Edu Lobo, Geraldo Vandré, Caetano Veloso, Jackson do Pandeiro, Elizeth Cardoso, Jair Rodrigues, Elis Regina and Paulo César Pinheiro, to name only a few of the best known.

In other words, capoeira music was present in MPB from the very beginning. Capoeira was undoubtedly becoming fashionable, and these recordings helped it to be accepted by society.

The spectacle of capoeira

The acceptance of capoeira by society is also visible in the growing number of capoeira shows on stage, in presentations and concerts promoted by associations, clubs and businessmen at that time – the 1960s and 1970s. Some of these shows, in Bahia and other states, were for tourists, but in Rio de Janeiro, many were aimed at a carioca audience, who were still unfamiliar with modern capoeira. As Ana Höfling (2019) has shown, in Bahia, bringing capoeira to the stage had a profound impact on the art itself.

All these events and launches were reported first by the press, soon by radio and television. As is well known among scholars, the art migrated from the police pages to the culture and sports pages, leaving a trail that makes it possible, today, to reconstruct that history. Capoeira was present on the radio, since the first recording of Almirante which went on air, in 1938, on Rádio Nacional. In 1963 the journalist André Lacé launched the first regular program about capoeira, Rinha de Capoeira.

Television also began to report on capoeira. Unfortunately the disorganisation of audiovisual materials in public archives still does not allow a systematic consultation of these records, a large part of which is probably lost forever. There is no doubt, however, that the relations between capoeiristas and the media were also fundamental to the destinies of the art, and therefore need to be investigated more systematically.

In this classic photo from Mestre Cabide’s collection, the Capoeira Bonfim Group, wearing their traditional striped shirt and white trousers, gathers for a presentation on TV Globo, in the 1960s.

Capoeira and the state

Another important dimension of the relationship between capoeira and broader society took place in the armed forces and the police. It is commonplace to refer to capoeira as resistance by the enslaved, and indeed it served that purpose in the times of slavery. But at least as far back as the War in Paraguay, we have had the figure of the capoeira-soldier. In Rio de Janeiro, during the Empire, many capoeiras joined the National Guard, the citizen militia that defended the slaveholding order. They also ended up joining the police or serving as henchmen and canvassing voters for the conservative and liberal parties, even during the Empire.

From at least the beginning of the Republic, a section of the Army took an interest in capoeira and tried to “redeem” it so that it would serve as a “national gymnastics”. From the anonymous O.D.C. to Inezil Marinho there were calls to incorporate capoeira into the physical education of soldiers and sailors. Masters Bimba and Artur Emídio, to cite only the two most famous examples, gave classes to Army and Navy recruits. Capoeristas were also part of the special police force created by the Vargas regime in 1933. In the 1960s and 70s capoeira was also present in the Military Police of Rio de Janeiro and Bahia (and I suppose in other states as well). The history of this complex relationship is still to be written.

In 1968 and again in 1969, the Brazilian Air Force organised two important capoeira symposiums bringing to Rio de Janeiro the most renowned capoeira mestres from Bahia to discuss the institutionalisation of the art. When the National Sports Council recognised capoeira as a sport, in 1972, many military personnel again became involved and contributed to the creation of the Brazilian Confederation of Capoeira (CBC) in 1992.

And the relationship with the State is not limited to the armed forces and the police. Capoeira has been part of the national sports organisation since the days of Vargas. The National Department of Brazilian Wrestling (Capoeiragem) was part of the Brazilian Boxing Federation, created in 1935, and subordinated to the National Sports Council (Decree Law No. 3199, from 14.4.1941).

Historical heritage

Beginning in the 2000s, the Heritage Department (now IPHAN) also became interested in capoeira, especially as UNESCO formulated policies to safeguard intangible heritage. This process has resulted in the inventory of the capoeira roda and the mestre’s craft, in 2008 in Brazil, and the capoeira circle by UNESCO itself, in 2014.

It is interesting in this regard to see how various groups within and outside the State have endeavoured to institutionalize capoeira, following different models: sometimes enshrining it as a sport, sometimes as Afro-Brazilian culture. As recent conflicts over regulation of the profession in the Brazilian Parliament show, this process is far from over.

In the same way, capoeira participated in social movements during the New Republic, for instance, with some groups becoming associated with the Black consciousness movement, which re-emerged in the 1980s. More recent is the important articulation of women practitioners within their groups, or in parallel networks, claiming equal rights in capoeira and fighting against “toxic” machismo and gender violence.

Finally, capoeira has developed a huge field of interaction with physical education and the health sciences. Teaching methods based on capoeira and capoeira as therapy are just two examples of the way the art has made its presence felt in these disciplines and fields. We hope, in the future, to have contributions to our blog covering all these topics (send suggestions to capoeirahistory arroba gmail.com).

In conclusion, we may say that the relationship between capoeira and society is a complex one, occurring in many dimensions and fields. There are reciprocal influences, exchanges and circulation of practices, knowledge and procedures. It is up to historians, social scientists and the mestres and practitioners themselves to reflect on this dialectic between capoeira and society at large. In a way, to write the history of capoeira is to write the history of Brazil.

Further reading:

Cabral, Sérgio. Nara Leão: uma biografia. Rio de Janeiro, Companhia Editora Nacional/Lazuli. Kindle Edition, 2008.

Höfling, Ana Paula. Staging Brazil: choreographies of capoeira. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2019.

Silva, Elton & Corrêa, Eduardo. Muito antes do MMA: O legado dos precursores do Vale Tudo no Brasil e no mundo (1845-1934), 2 vol. publicados, edição Kindle, aproximadamente 2019-2020.

“Roda de Capoeira”, Nara Leão, LP Opinião, 1964. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lfLcrQv_CVU

![O Malho [1910-08-20-p.49] Foto de Ciriaco O Malho [1910-08-20-p.49] Foto de Ciriaco](https://capoeirahistory.com/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/O-Malho-1910-08-20-p.49-Foto-de-Ciriaco-pxbs0csqq6zm0de1b2bcdtqwuqo9y5sxoasdwp7s80.jpg)